The question of reparations largely interests me. One of the best readings I had so far speaks of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC): Country of my Skull by Antjie Krog. The book has been with me since many years, first as I was coordinating Bruxelles nous appartient – Brussel behoort ons toe (Brussels belongs to us), a storytelling project of the Brussels’ inhabitants who’s stories are not often heard. Later, as my interest shifted towards colonization, racism and the construction of images of the ‘other’, it re-became instant and I started reading it all over again. It is a wonderful book, not only because it has an intriguing cover, a lightness (literally) and a nice touch of sketchbook-like paper, but of course mostly because of its contents and style. Antjie Krog treats the subjects of the TRC broadly and deeply, from the organization of the commissions over the politics, the power relations, the ethical and psychological questions, her personal story within it and the discussions with her colleagues. The bulk of the book consists, like the hearings of the TRC, of the detailed accounts of injustices done, recounted by the victims and sometimes the wrongdoers. It is the stories of mothers seeking information about disappeared children, of not recognizing their maltreated corpses, of being lied to and despised by the authorities. These parts are very disturbing. It is what was all over the South-African media from 1996, two years after South-Africa’s first free elections, until 1998. The nation discovered the truth on their traumatic past.

The question that might interest us most is if the TRC really brought reconciliation and, thus, peace. From the book I understand that it is only partly the case. The mostly black victims have expressed themselves. Some wrongdoers, both white and black, did the same with amnesty in view. But the big fish ‘sent their cat’; leaders like De Klerk en Botha were very hard to convince to show And up at the hearings in person, and mostly they did not admit their personal involvement in the many cases of mass murder, maltreatment and torture of innocent people by their services. ‘But you must have known’, say the victims and the journalists.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, chairman of the commission, had worked hard to get the white leaders on the stand. He was very motivated: “for reconciliation, we need everyone” and, elaborating on the job he was given: “You see, we can’t go to heaven alone. If I arrive there, God will ask me: “Where is De Klerk? His path crossed yours.” And he also – God will ask him: “Where is Tutu?” So I cried for him, I cried for De Klerk – because he spurned the opportunity to become human.”

Not only are the important white perpetrators absent, if they show up, they often come with lawyers and they do not show their emotions. Antjie Krog cites clinical psychologist Nomfundo Walaza. ‘What makes me angry is that whites are privatizing their feelings. If you as a black person cry, you cry alone at the hearings. If you are angry, there is no perpetrator to direct that anger against verbally- they hide in their suburbs, they hide behind their court interdicts and legal representatives. The pain of blacks is being dumped into the country more or less like a commodity article – easy to access and even easier to discard’.(p244)

And also: ‘Guilt is such a useless thing, (…) Guilt immobilizes you. (…) I prefer shame. Because when you feel shame about something, you really want to change it, because it’s not comfortable to sit with shame.”(p.244-245)

So how does this work for reconciliation? What is done about the past? When discussing colonialism, people often refer to the Holocaust and the global recognition of its horrors. So does Antjie Krog: I take a Jewish colleague aside: “What kind of reparation was done by the Germans?’ He provides an impressive list, ranging from pensions and free transport, to leaders kneeling at Jewish memorials. And money – money from the Federal Republic of Germany was the largest contributing factor to the full industrialization of Israel… I listen perplexed, thinking about the unimaginative document on reparation workshopped some months ago. They could come up with nothing more inspired than a lump sum of money. No special study fund, housing subsidy scheme, pension provision, medical assistance – just a sum of money that the government has to dish out. And if it cannot afford to do so, the Commission can wash its hands and say, ‘It’s not our fault’. (p.197)

(I still cite Antjie Krog:)

I also know better than to ask my Jewish colleague whether anyone was forgiven on the basis of reparation. Is contrition in the form of reparation just as futile as denial?

And suddenly it is as if an undertow is taking me out…out…and out. And behind me sinks the country of my skull like a sheet in the dark – and I hear a thin song, hooves, hedges of venom, fever and destruction fermenting and hissing under water. I shrink and prickle. Against. Against my heritage thereof. Will I forever be them – recognizing them as I do daily in my nostrils? Yes. And what we have done will never be undone. It doesn’t matter what we do. What De Klerk does. Until the third and the fourth generation. (p.197)

There is much more to say and to cite from the book. Let me give you the reference of the copy I cite from:

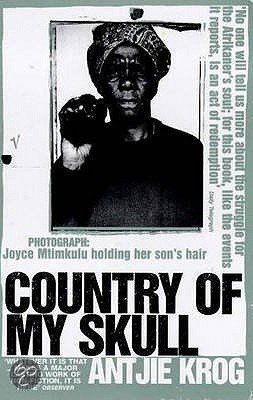

Antjie KROG. Country of my skull. Vintage, London, 1999, 454 p.