Before this research, I thought ‘Human Zoo’ was a way of saying things, based on the way we gaze at the animals in a zoo and metaphorically transmitted to how we gaze at the ‘other’ – the colonial other. My imagination had however led me far too far: the Human Zoo is a true fact of history.

The German Carl Hagenbeck started it. He was an internationally successful supplier of animals to zoos. In 1875, he had a herd of reindeers brought to Hamburg by authentic Sami complete with sledges, tents, utensils and dogs. So many people came to see, that Hagenbeck organised a tour. The Sami were examined by the Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte. Later he had Nubians and Inouit. It became his career, and of his sons. Between 1875 and 1940, in Germany alone, 400 of these groups were exhibited.

From 1907 on, he had his own zoo in Hamburg.Confirming the clichés

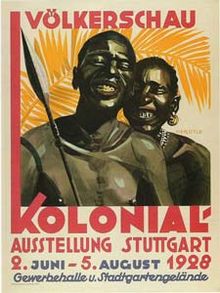

The people were exhibited in zoos, but also at theatres, fairs and at colonial and world exhibitions.

They had to show their ‘authentic’ lives: as savages, as singers and dancers or as ‘freaks’, like women with lip discs. Their wildness was often accentuated in the texts and drawings on the posters announcing the shows. Their performances had to meet the images the western public already had of the peoples. The clichés were at least as old as 1760 (but based on much older ideas), when Carl Linnaeus published his categories of animal species, where he had distinguished 4 kinds of humans. At the top were the superior Europeans, followed by the Asians, Americans and Africans. Homo americanus was red with black hair, little beard growth, was stubborn and free, with red painted stripes, and was guided by superstition. Homo europaeus was white, had long hair, blue eyes, was tall, heavily muscled, intelligent, wore tight clothes and had himself ruled by governments. Homo asiaticus was yellow, melancholic, had black hair and brown eyes, was irritable, wore loose clothing and was led by opinions. Homo afer was black, cunning, lazy, with black curly hair, and led by impulses. The women knew no shame and had plenty of milk. Homo monstrosus was a mixed category of dwarves and big lazy Patagonians.

If there were contracts with the exhibited, they often stipulated that they had to behave accordingly to the expectations of the white public. They had to be wild and dangerous.

One of the biggest successes were the Ahoshi Amazons from Dahomey, a female military section, although it were Ashanti women who came to Europe for the shows. These were announced as ‘beautiful women’, who in the blink of an eye could transform into bloodthirsty furies. The public was fascinated and the women played their role.

Different was the display of the ‘very lowest of mankind’, a group of eight Australians, announced as the “strange, disfigured and most brutal race ever lured from the remote interior wilds”, and as cannibals. At the Frankfurt Zoo, 1885, the public could only see five frozen Australians under a blanket, ashamed of all the things that were said about them.

There are also many stories of North American natives, who adapted to the clichés formed after the images of the Sioux: teepees, feathers, braids, stripes painted on the face… a group of Mohawks adapted their show. A tour of Bella Coola natives was not successful at all, their clothing not at all responding to European expectations.

(after the book ‘De exotische mens’ pp 37-65)

The Hagenbeck shows

Hagenbeck was a rather good employer: he concluded detailed contracts with the exhibited and, since the death of his ‘Eskimotruppe’, saw carefully to it that everybody was vaccinated. He also took care that no assertive people came, no ‘troublemakers’ nor drunks, neither people who spoke western languages. He looked for people he found graceful, artisans and performers, rather than ‘freaks’ like women with lipdishes or disfigured people. A group had to represent a society, with an equilibrium in sexes and ages. Its members had to meet the ‘authentic type’ of their people.

The groups were mostly motivated by money. Some wanted to escape poverty, others were better off and made demands. The Sami had for example negociated that replacements were provided to watch their herds at home while they were on tour.

Hagenbeck always based his shows on the same ingredients: music, dance, fighting, the ties between the ‘savages’ and animals. The structure of the show consisted of three acts: first the daily life, then an event involving fighting (an attack on the village, an abduction of women,…) and third a piece ritual or a marriage ceremony with music and dance and always a parade of the savages with wild animals. The setting was a reconstructed village in front of a canvas on which the icons of a society were painted: pyramids, temples,..

After the tour, the props (artefacts) brought from the countries, were often given or sold to musea. In turn, the musea often provided the shows with an aura of science.

Hagenbeck also knew Barnum, the American master of freakshows. He had been one of his suppliers of exotic animals since 1872.

(after Zoos Humains pp 81-88)